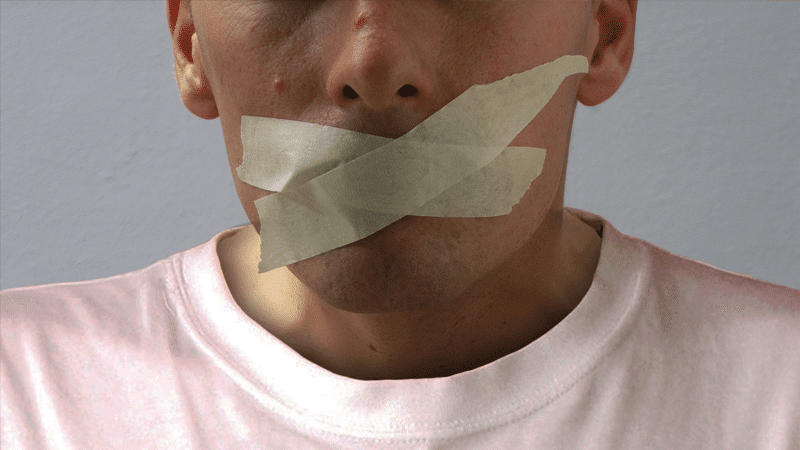

The Government is in danger of strengthening the hand of ‘Big Tech’ censors through its Online Safety Bill, several senior columnists are warning.

James Forsyth, political editor for The Spectator, fears the Bill will create a “dragnet” filtering out free speech for years, while veteran journalist Melanie Phillips predicts the rise of an online thought police to censor free expression.

In an editorial, The Times said the legislation posed a threat to “citizens’ speech” by giving technology companies licence to manage online content.

Problems in cyberspace

Writing in The Times, Forsyth described the Online Safety Bill as arguably “the most consequential piece of legislation this government will ever pass”.

Under the Bill, he said, social media companies would be required to ‘censor by proxy’ online content deemed to be ‘legal but harmful’.

The columnist continued: “This unprecedented mechanism sets up a legal obligation for tech firms to go beyond the law.” He added: “You can spot the problems with this plan from cyberspace.”

the most consequential piece of legislation this government will ever pass

Forsyth reported: “One influential figure in the tech scene says privately that in order to stay on the right side of the law he would be prepared to take down 10,000 pieces of content to catch one that might incur the wrath of the regulator.”

Non-crime ‘hate’

In the same newspaper, award-winning journalist Phillips raised similar concerns over the “introduction of a ‘legal but harmful’ category for the removal of content”.

Phillips warned: “This threatens to become the online equivalent of the ‘non-crime hate incidents’ invented by the College of Policing in its genuflection to identity politics.”

the most consequential piece of legislation this government will ever pass

She concluded: “Truth is discovered by opening up legally permitted discourse, not limiting it. Censorship is never the answer.”

‘Attack on democracy’

The Times cautioned: “micromanagement of online speech by big technology companies, with little or no accountability, may amount to an attack on liberal democracy”.

It argued that the Bill failed to get “all the difficult balances right”, was ill-defined and left “enforcers to make difficult subjective choices”.

the most consequential piece of legislation this government will ever pass

By way of illustration, the editorial explained: “A tweet that one reader perceives as robust and healthy challenge to their point of view may be perceived by another as an attack that threatens their mental health.”

It added: “In the febrile debate on transgender rights, for example, accusations that speech has harmful consequences are commonplace on all sides.”

Free speech

The concerns are in keeping with those raised by The Christian Institute, which has called for radical amendments to the Bill.

The Government has introduced an Online Safety Bill to bolster regulation of the internet. It risks unfashionable views – like biblical teaching on sexual ethics – being censored because some people don’t like them. This could profoundly limit religious freedom and debate. If something is legal to say offline, it should be allowed online.

In a briefing for MPs it explained that there is currently no clarity as to what legal content will be considered ‘harmful’. It also argued that, because tech companies could be fined up to ten per cent of their annual global turnover if they fail to uphold their new duties, they are likely to censor “far more than they need to”.

Queen’s Speech

Following the Bill’s inclusion in the Queen’s Speech, parliamentarians warned the Government’s Online Safety Bill risked legal speech being censored online.

Joanna Cherry, a QC and SNP MP for Edinburgh South West, said there is “significant danger” that, as drafted, the Bill will lead to “censorship of legal speech by online platforms” and that it will “give the Government unacceptable controls over what we can and cannot say online”.

Cherry said she shared Liberal Democrat Jamie Stone’s worries that the definition of what constitutes ‘legal but harmful’ will be contained in secondary legislation, rather than primary, meaning it will receive little parliamentary scrutiny before being voted through or rejected.

A number of Peers, including Lord Hunt of Kings Heath, also raised concerns about the Bill.