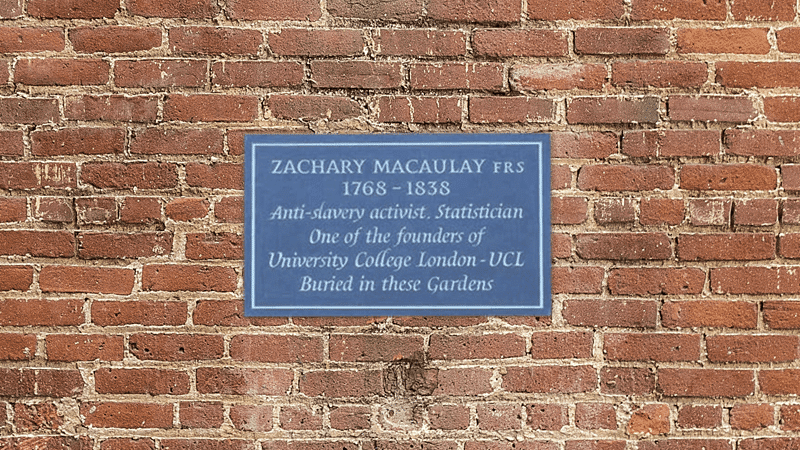

Two-hundred and fifty years since his birth, one of the men who fought to end slavery has been honoured with a memorial plaque in St George’s Gardens in London.

Zachary Macaulay was born in Inveraray in 1768, but after getting a job in a merchant’s office in Glasgow, he spent much of his youth drinking.

Aged 16, he left Scotland for Jamaica, where he would become an overseer at a sugar plantation.

Brutal reality

There he was confronted by the reality of slavery. The slaves often worked for 16 to 18 hours a day, discipline was brutal, and many slaves lost fingers to machinery.

Three years was as long as many survived in the terrible conditions, and while initially Macaulay had been horrified, he soon became callous and indifferent to the problem.

He returned to Britain in the late 1780s, when he lived with his sister Jean, and her husband, Thomas Babington.

Babington was an evangelical Christian, and though Macaulay had been brought up in a church-going home, it was he who brought the young Scot to Christ.

Clapham Sect

He was soon introduced to Babington’s friends, William Wilberforce and Thomas Gisborne, who were among other members of the Clapham Sect campaigning to abolish slavery.

His experience working on a plantation proved invaluable to the group, who invited him to visit Sierra Leone, where they planned to create a safe haven for freed slaves.

He became Sierra Leone’s Governor in 1794, aged just 26, and worked hard in the face of much adversity to keep the colony alive, even spending time as a French captive.

First-hand experience

When he finally returned to England, Macaulay took a tremendous detour via Jamaica on a slave ship in order to experience the conditions first hand.

Upon his return, he used his phenomenal memory of first-hand experiences to support abolitionists during the parliamentary inquiries.

One journalist has said: “Macaulay supplied the statistics and facts for every single speech made in the House of Commons and the House of Lords during the decade it took to see the abolition of slavery across the empire.”

His biographer Dr Iain Whyte remarked: “He collected the material and Wilberforce used it. I would have to say strongly that it would have taken longer to abolish slavery but for the campaigning of people like Zachary.”

Final push

The Act for the Abolition of the Slave Trade was passed in 1807, and Macaulay spent many years fighting to enforce the law.

He died in 1838, five years after Parliament finally voted to abolish slavery in British territories.