II – God’s Grace

Next in our series on the Reformation, Dr Sharon James, Social Policy Analyst for The Christian Institute focuses on Martin Luther.

Can I be certain that I am right with God?

The message of the Gospel is ‘Yes!’ Not because of anything I do. ‘Yes’ because of what Christ has done for me.

Martin Luther discovered this first hand. He was born in 1483 near Mansfeld in central Germany, and after studying law, he entered the Augustinian monastery at Erfurt.

Soon after, he was sent to lecture at the University of Wittenburg where he became Professor of Biblical Theology, and also preached regularly at the town church.

Although he diligently studied, preached, and followed the routine of a monk, Luther never attained the peace with God that he longed for. He particularly struggled with Romans 1:17.

For in the gospel a righteousness from God is revealed, a righteousness that is by faith from first to last, just as it is written: ‘The righteous will live by faith.’

Romans 1:17

Luther later wrote:

For I hated that word ‘righteousness of God,’ . . I had been taught to understand [that this means that] God is righteous and punishes the unrighteous sinner. At last light began to shine: There I began to understand [that] the righteousness of God is that by which the righteous lives, by means of a gift of God, received simply by faith.

‘The righteousness of God’ means the gift of Christ’s righteousness with which the merciful God justifies us by faith. Now I felt that I was altogether born again . . . I extolled the sweetest word ‘righteousness’ with a love as great as the hatred with which I had before hated it. That place in Paul was for me the gate to paradise.

Luther’s call to embrace salvation by grace was rejected by the church hierarchy. He first came to the attention of the Pope when, in 1517, his ‘95 Theses’ or ‘points for debate’ about papal indulgences were circulated throughout Germany.

Luther excommunicated

Luther was excommunicated in 1521, and summoned before the Imperial Parliament at Worms. When asked to recant his writings, Luther declared:

Unless I am convinced by Scripture and plain reason my conscience is captive to the Word of God. I cannot and I will not recant anything, for to go against conscience is neither safe or right. God help me. Amen. Here I stand. I can not do otherwise.

To defy the Pope and to defy the Emperor meant certain death. But the Elector of Saxony used his influence to protect Luther. Luther was hidden away in the Elector’s Castle, where, in just eleven weeks, working from the Greek text, he translated an exceptionally beautiful German New Testament.

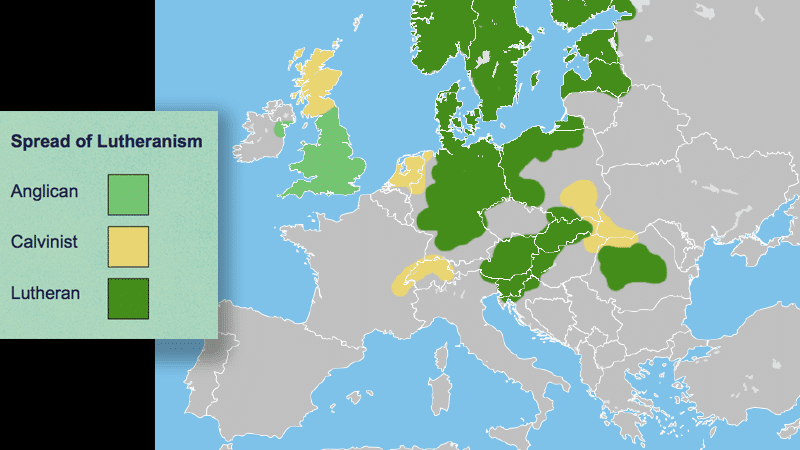

After ten months, Luther returned his lecturing and preaching at Wittenburg. He organised church reform in Saxony, even as others who adopted reformed ideas pushed through church reform in other territories, including Sweden and Denmark, England, and Scotland.

Luther depended on the Elector of Saxony for the furtherance of the Reformation – he was still operating in the context where church and state were inseparable. He and the other so-called ‘magisterial’ reformers depended on the civil authorities to push through reform. An obvious problem was that, in time, territories that were officially ‘Lutheran’ would be filled with nominal Christians.

Luther’s desire for political stability provoked him to an intemperate exhortation to the princes to crush a peasant’s revolt in 1524-5. The aristocracy and their armies slaughtered up to 100,000 of the 300,000 poorly armed peasants and farmers. In similar vein, tragically, we have to note that Luther wrote a shocking and violent tract against the Jews.

All this was bound up with the identity of the Church with the political territory. And the uniting of church and state resulted in the horrors of war between different religious factions.

Concept of vocation

In some ways Luther never shifted far from the medieval mindset, in particular the identification of church and state.

But positively, Luther revolutionised the concept of vocation. The Catholic Church had restricted this to monks, nuns, and priests. Luther applied vocatio to all lawful occupations, and all the various roles that we play. We can live all of life for God’s glory.

Luther also revolutionised the concept of family as a vocation. The Catholic Church held that celibacy was the superior state. Luther and other reformers pointed to the biblical teaching that marriage is blessed by God.

Luther led by example. Aged forty-two, he married twenty-six year old Katherine von Bora, a former nun. They had six children, and their family life provided an attractive role model, promoting the idea that marriage is a God-given calling.

Martin Luther was flawed. He did not get everything right. But he is remembered as the one who really did grasp salvation by grace. Fittingly, after he died, it was discovered that the last words he ever wrote were ‘we are all beggars now’. That is how we all stand before God.

The truth of justification by faith transformed the lives of men, women, young people and children all over Europe during the sixteenth century. It is still transforming lives today.

This is an abridged version of a talk given by Dr Sharon James at Word Alive 2017, the full transcript including footnotes is available here: www.reformation-today.org/articles-of-interest/the-reformation-rediscovering-the-power-of-the-gospel-a-series-of-papers-by-dr-sharon-james-presented-at-the-word-alive-conference-2017-part-ii