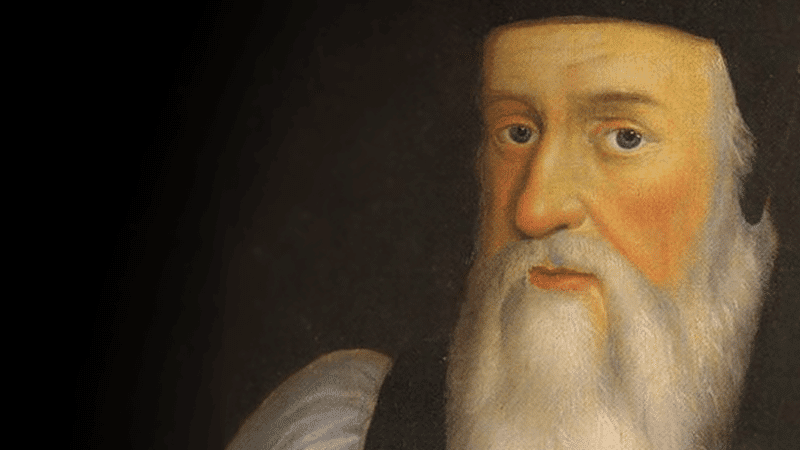

Thomas Cranmer: The master strategist of the English Reformation

The English Reformation went through turbulent times during the Tudor period. But during this time Thomas Cranmer was a key figure used by God to create long-lasting change in the English Church.

The Christian Institute’s third lecture in its Autumn Lecture series on the English Reformation focused on the life of the influential reformer, regarded as a master strategist and the driving force behind reform.

Revd Dr Richard Turnbull shed light on the important works of the man perhaps better known for the manner of his death than for the achievements of his life.

The King’s ‘great matter’

While no single event can be attributed as the beginning of the English Reformation, the King’s “great matter” certainly proved a catalyst for large-scale reform.

Henry VIII’s desire to divorce Catherine of Aragon meant he was open to teaching which challenged the power of Rome.

Thomas Cranmer, along with fellow reformer Thomas Cromwell, seized the opportunity to gain Henry’s backing for change.

Inconsistent progress

Cranmer was rewarded by being named the Archbishop of Canterbury, but Henry was often in two minds about pushing reform: one moment supporting it, the next, persecuting reformers.

Thousands of Tyndale Bibles were in circulation, and Henry even commissioned an English translation himself, but later backtracked and ordered every Bible be chained up, only to be read by priests.

While Henry was inconsistent in his support for reform, Protestantism was largely given opportunity and freedom to grow during the latter part of his reign.

Book of Common Prayer

It truly began to flourish when Henry’s Protestant son and heir Edward VI ascended to the throne in 1547 aged just nine.

Cranmer moved swiftly, publishing two prayer books in quick succession, both in English. The first, printed in 1549 was put together under time constraints and so was not as clearly reformed as it could have been, but this was put to rights in the 1552 Book of Common Prayer.

They would replace the teaching on transubstantiation, strip out prayers for the dead, and add in the Ten Commandments, which Cranmer believed should be recited weekly.

Since so many parish priests were barely literate at that time, Cranmer also provided a book of homilies. He reasoned that if preachers couldn’t write sermons, then sermons would have to be provided for them.

Execution

Thomas Cranmer’s work led to a reformed and transformed church – but it was a church which suffered during Mary I’s five year reign.

Staunchly Catholic, Mary had over 300 Protestants executed, among them Cranmer.

Refusing to flee abroad like many other reformers, he was tried for treason in 1553 and found guilty.

Over the next three years he was interrogated and after watching his friends, the Bishops Latimer and Ridley, burned at the stake in Oxford, he eventually recanted.

Yet when on trial, and expected to declare his adherence to Rome, he instead affirmed reformed teaching, and denounced the Pope as an antichrist.

Cranmer was burned at the stake but his legacy lives on in the nation even today, not least through the Book of Common Prayer.