IV – God’s People

In the final part of our Reformation series, Dr Sharon James looks at freedom of conscience and religion.

Ulrich Zwingli was born in Switzerland, in 1484. Like Luther, as a young Roman Catholic priest he studied the Greek New Testament and came to a deep experience of salvation by grace.

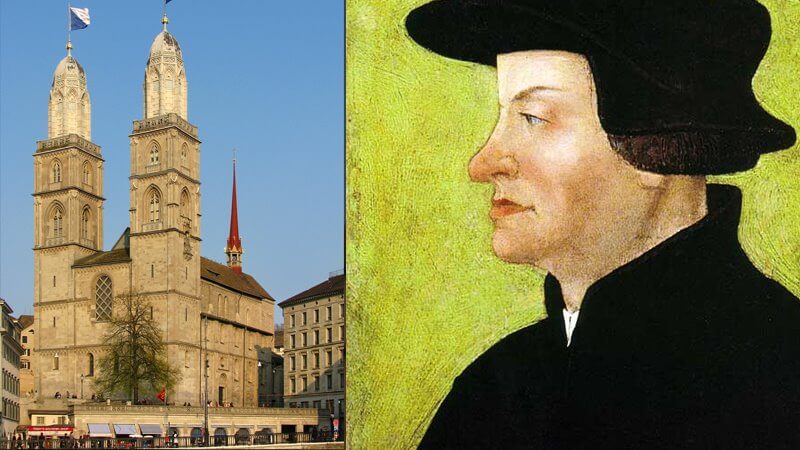

On New Year’s Day 1519, Zwingli took up the post of preacher at the Cathedral in Zurich.

He stunned the congregation when he announced that he would preach systematically through the whole New Testament. He preached boldly against those elements of the Roman Church he believed to contradict the Word of God.

Zwingli attracted a keen group of evangelical scholars to Zurich.

Like him, they believed that the Bible should be the only authority for doctrine and church practice. One was a scholar called Conrad Grebel, others included Felix Manz and George Blaurock.

Zurich was ruled by a Mayor and a 24-member Council. In 1522, the Council decided to break free of Catholic rule. Controversy raged about how quickly reform should proceed.

In 1523, Zwingli agreed that the Council should determine whether or not images should be retained in churches, and for how long the Mass should be retained.

Civil authority and church practice

Back in 1520, Zwingli had stated that the civil authority had no place determining church practice. Now he conceded that the only way the Reformation could take root was if the civil magistrates enforced it.

Zwingli, in the view of Grebel and his friends, was failing to operate on the principle of ‘Sola Scriptura’, Scripture alone as the final authority.

And, as Grebel and his friends studied Scripture, they also became convinced that the Church is made up of those who profess repentance and faith. In their view, infants could not do either of those things. In January 1525, Conrad and his wife refused to take their new baby Rachel to be christened.

But this was regarded as a crime, as infant baptism was not just a religious practice. It was a civil obligation, marking membership not just of the Church, but of the state.

Early on in his ministry, Zwingli had accepted:

If we were to baptise as Christ instituted it, then we would not baptise any person until he reached the years of discretion, for I find it nowhere written that infant baptism is to be practised.

But, he had gone on to say:

If however I were to terminate the practice (infant baptism) then I fear that I would lose my preband [position]… One must practice infant baptism so as not to offend our fellow men.

When the Council ruled that anyone who failed to present their babies for baptism should be expelled from the city, Zwingli supported this ruling.

Grebel and his friends believed that, for Zwingli, expediency had – again – triumphed over ‘Sola Scriptura’.

Torture

A few days later, a group of believers, including Grebel, Mantz and Blaurock openly confessed repentance and faith. Each was then baptised as a believer.

The Council accused the group of the crime of ‘anabaptism’ or ‘rebaptism’. Grebel et al never accepted this label. They called themselves ‘Christians’ or ‘brethren and sisters’.

But the Council pronounced that anyone who practised ‘anabaptism’, should recant.

Torture could be be used to secure recantation. If they did not recant, non-citizens should be banished, and citizens should be killed.

Zwingli endorsed this ruling.

In 1524, one advocate of believer’s baptism, Balthasar Hubmaier, wrote a powerful plea for religious toleration entitled: Concerning Heretics and Those Who Burn Them. He was arrested and tortured in Zurich. Hubmaier bitterly regretted his forced recantation. When re-captured, he stood firm to his beliefs, and was burned at the stake in Vienna.

On January 5, 1527, Felix Manz was sentenced by the Zurich authorities to be drowned. Zwingli watched as his former follower was killed, commenting: “Let him who talks about ‘going under’ go under!”

On 24 February 1527, a group of the brethren gathered in the German town of Schleitheim, and adopted the Seven Articles of Brotherly Union. This confession affirmed that magistrates are ordained for the punishment of evil doers, but within the Church, the ultimate punishment is excommunication. Magistrates are not entitled to use the death penalty for spiritual offences. The Bible, not the magistrate, must order church practice. The Confession affirmed membership of the Church is for professing believers, not everyone in a territory.

Unity and stability

The evangelical Anabaptist movement spread rapidly from 1527 onwards, through Switzerland, South Germany, Austria, Eastern Europe and the Low Countries.

In 1529 the Diet of Speyer was convened. It ordered that ’every Anabaptist and re-baptised person of either sex should be put to death’. And through the following century Lutherans, Reformed, and Catholics all agreed that to preserve societal stability, all infants should be baptised, by force if necessary.

When some believers refused to baptise their children, this was regarded as a threat to the unity and stability of society. When these believers denied that the civil magistrate had the power to enforce true religion, it was assumed (wrongly) that they denied that the civil magistrate had any power at all. This was regarded not only as heresy but treason. Traitors could be punished by death, enforced by the civil authorities.

That partly explains the hostility evoked towards rebaptised believers.

In addition, a wide spectrum of ideas all went under the collective insult ‘anabaptist’.

At the one extreme there were the ‘rationalists’, including men such as Michael Servetus, the anti-Trinitarian who was burned at the stake in Geneva.

At the other extreme there were ‘inspirationists’, enthusiasts who were full of zeal for immediate reform. Some became taken up with the expectation of the coming of Christ and urged violent steps to inaugurate the kingdom.

Pseudo-communistic state

Famously, one group attempted to set up the ‘Kingdom’ in the city of Munster in North West Germany. In 1534, they founded a pseudo-communistic state, the ‘New Jerusalem’. The shocking events there gripped the collective attention of Europe like a running soap opera. The town was captured in 1535 and the leaders were tortured to death.

This tragic drama was used to blacken the name of all ‘anabaptists’ for centuries to come.

However, many others, also labelled ‘anabaptist’, were neither rationalist nor inspirationist.

They, like the group in Zurich, did not believe that the state should control the Church. They believed that the people of God are a gathered church of repentant sinners who profess faith in Christ, rather than a nation state based on blood. They believed that church membership should be voluntary, and that the mark of entry is repentance and believer’s baptism.

In the face of fierce persecution, many adopted an ethic of peaceful non-resistance.

For example in 1569 a Dutch Anabaptist, Dirck Willems, escaped from his home, but he was chased by officials. Coming to a frozen dyke he crossed safely. His leading pursuer fell through the thin ice. Turning back, Willems saved him from certain drowning. Despite this, he was arrested, and burned slowly at the stake.

The conviction that church membership should be voluntary, not forced, goes inseparably with insistence on freedom of conscience. The anabaptists were ahead of their time in advocating religious freedom.

The first full defence of religious liberty in English, The Mystery of Iniquity, was written by the Baptist Thomas Helwys in 1612.

The next landmark defence of religious freedom, The Bloody Tenet of Persecution, was written in 1644 by the Baptist Roger Williams. He argued that force never produces genuine faith, that forced worship is abominable to God, and that the magistrate has no place in controlling the Church.

Williams is remembered as the founder of ‘Providence’ (Rhode Island), the first colony which deliberately set out to practice separation of church and state and freedom of conscience and religion.

Today, whatever our differing convictions about baptism or establishment, we would all unite to defend this principle of freedom of conscience and religion.

This is an abridged version of a talk given by Dr Sharon James at Word Alive 2017, the full transcript including footnotes is available here: www.reformation-today.org/articles-of-interest/the-reformation-rediscovering-the-power-of-the-gospel-a-series-of-papers-by-dr-sharon-james-presented-at-the-word-alive-conference-2017-part-iv

Read The Reformation I God’s Word: ‘Sola Scriptura’, II God’s Grace and III God’s Glory.